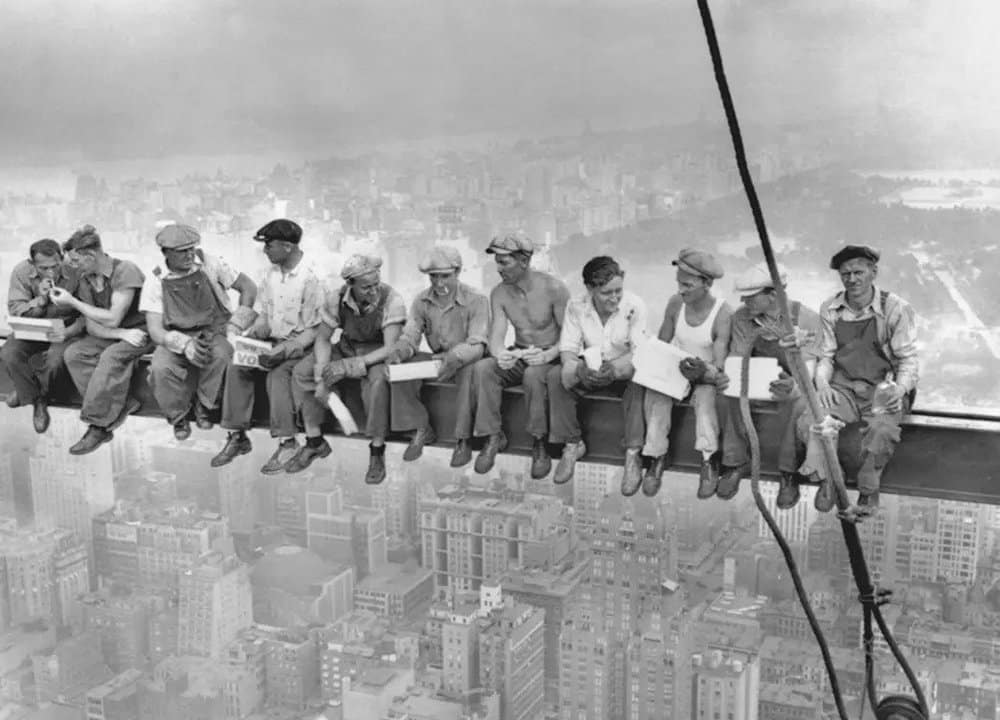

The picture is iconic: eleven men cloaked in the grainy black-and-white photography of 1932, seated with their legs dangling from their I-beam perch, naked to the whims of gravity while they casually share stories and cigarettes. A bird’s-eye view of the Depression-era New York skyline and Central Park forms the background. It’s called “Lunch Atop a Skyscraper.” Shot for publicity purposes on what would become the 69th floor of Rockefeller Center, the men were nonetheless real ironworkers, and their fearlessness isn’t so much celebrated by the viewer as assumed. What’s really being celebrated here, many pundits have said, is the country’s resilience in the face of the Great Depression.

Americans have a tendency to romanticize risk-taking, and despite the casual confidence of the men eating their lunch atop the skyscraper with virtually no safety gear in sight, the risk was front-and-center in their minds. As author John Rasenberger put it “The pay was good. The thing was, you had to be willing to die.” Contractors of the time reportedly built an allowance for one death for every ten floors of building height into their accounting, and 2% of workers died every year. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics didn’t begin its Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries until 1992, but it certainly seems likely that falls were the leading cause of fatal injuries in 1932, despite the incredible sense of balance shown by those aerial lunch-eaters.) There’s nothing romantic about risk-taking when you’re the family of a worker who had fallen to his death under such circumstances.

And so despite our awe and admiration for the men in that photo and all the others they represent, we’re a little appalled by it as well.

The Modern Era is different, but…

Fortunately, the construction industry has made great strides in keeping workers safe since 1932. The fatal injury rate in 2019 was 9.7 per 100,000 workers – or about 1/200th the rate in 1932. But then, it’s tough to take pride merely in outperforming the safety record of a century ago, when American culture had set the bar so low that workers were treated as “as interchangeable pieces, like pawns on a chess board.”

When that rate of 9.7 deaths is put in a modern context, 2019 was not a good year for construction worker safety, especially among construction laborers. The fatality rate had been trending downward slightly between 2011 and 2018, only to see an increase in 2019. And falls remain the most frequent type of fatal accident, accounting for a third of construction deaths. American business culture no longer treats worker wellbeing as a matter of simple accounting, and so no one in the construction industry is complacent about statistics like this, nor about the number of safety violations that still persist. While not all accidents, fatal or otherwise, are the results of safety violations, the list of the most common violations includes general fall protection, scaffolding, and ladders.

We can fix scaffolding and ladders. We can do a better job of training workers to guard themselves against potential falls. We can fix every item on the list of frequent safety violations. But maybe the overarching safety fix that’s needed has less to do with defects in the actual equipment workers use to climb up and down and more to do with making better use of a piece of equipment that’s seldom given its proper due: two-way electronic communication systems, with headsets and receiver/transceiver combinations.

The key to preventing accidents

How many construction-site accidents are caused by literal violations of safety codes like defective scaffolding or workers taking risks expressly forbidden by training? Fewer, we believe, than the number resulting from a unique convergence of circumstances that can’t be anticipated by any pre-ordained rules. And the key to preventing those accidents is clear, spontaneous communication. A worker stepping into a potentially risky situation may not have the perspective that a co-worker has from just a few yards away. In those circumstances a simple “Heads up!” could be the difference between a safe and unsafe choice – or between life and death.

But there are two factors hindering communication on a construction site – noise and distance. Only when all workers are equipped with two-way headsets can that clear, spontaneous communication be assured. The headsets fit comfortably under a construction helmet. The ear coverings help block out ambient noise, but more importantly, the speaker’s voice is heard directly in the listener’s ear, with no lag, no loss of volume due to distance, and no interference.

Who knows? If two-way communication systems had been available in 1932, someone near the photographer’s perch just might have told those eleven workers “Go find a safer place to eat your lunch.” The headsets may have cost us an iconic photograph, but they may have saved more than one life.