Brutalist architecture, starting in the mid-20th century, marks a significant shift in design. This style features monolithic structures, dominant forms, and extensive use of raw materials like concrete. With its rough and exposed surfaces, Brutalist architecture creates a dramatic, impressive, and often provocative appearance.

The term “Brutalism” comes from the French “béton brut,” meaning “raw concrete.” This architectural style adopts a fundamental approach, leaving building materials and structural elements undecorated. It challenges traditional ideas of beauty and focuses on the integrity of form and material.

Origins of Brutalism: Historical Context and Emergence

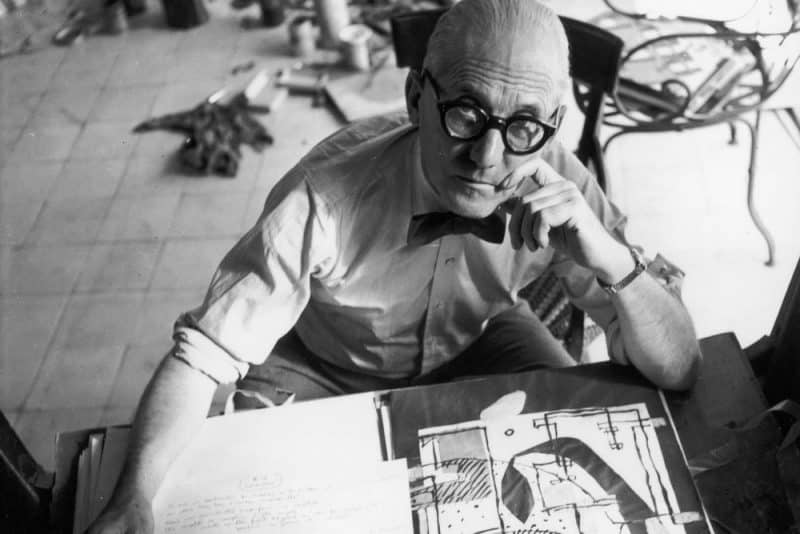

Brutalism emerged in the post-World War II period as a reaction to the optimism and lightness of mid-20th century modernism. The need for rapid and economical reconstruction after the war greatly influenced its development. Le Corbusier, a renowned architect, played a significant role with his pioneering use of raw concrete in designs like the “Unité d’Habitation.”

In the United Kingdom, architects Alison and Peter Smithson were key figures in promoting Brutalism. They combined functional social needs with stark geometric aesthetics. Their work emphasized natural, exposed, and untreated building elements, aiming to create buildings that were both functional and true to their construction methods.

Characteristics of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture primarily features extensive use of concrete. Designers favored this material for its rough, unfinished, and economical appearance. Concrete often retains its raw state, displaying the imprints of wooden molds and the texture of poured concrete.

The style showcases strong geometric shapes. Brutalist buildings frequently feature angular or curving elements that convey a strict and monumental presence. These structures often span large areas, creating an overwhelming sense of size and power.

Light and shadow play significant roles in Brutalist design. Deep recesses and projecting forms create dynamic plays of light that change throughout the day. This approach highlights the raw appearance of construction materials, keeping them visible and celebrated.

Functionality and Aesthetics in Brutalism

The core of Brutalist architecture lies in its focus on functionality. Architects designed every part of a Brutalist building with purpose and efficiency in mind. This philosophy is evident in the visible structural elements like pipes, beams, and other construction components.

These components serve as both basic structural units and integral parts of the design. This structural expressionism embodies the movement’s philosophy. Brutalism pioneers the idea that form and function are one, and beauty comes from the raw, tangible reality of the materials.

Social and Cultural Impacts of Brutalism

Brutalism also had significant social and cultural implications. Designers often associated it with social housing projects, educational institutions, and public buildings. The straightforward, unpretentious nature of Brutalism reflected ideals of social equality and democracy.

However, the style’s association with large-scale, utilitarian buildings led to some criticism. Many perceived Brutalist structures as oppressive and harsh. Despite this, the style aimed to create inclusive and functional spaces for the community.

Examples of Brutalist Buildings

Globally, Brutalism has produced many impressive buildings. The Barbican Centre in London is a major symbol of Brutalism. It combines a strong, monumental appearance with a functional cultural complex.

In the United States, Boston City Hall exemplifies Brutalism’s use of massive concrete structures for public authority. Canadian architect Moshe Safdie’s “Habitat 67” is another notable example. This project blends modular housing with the raw beauty of concrete, challenging traditional residential styles.

These structures demonstrate the global influence and flexibility of Brutalist architecture. They embody both awe and provocation through their use of raw materials and bold forms.

Controversies Surrounding Brutalism

Brutalist architecture remains a highly debated design style. Public opinion on these massive concrete structures varies greatly. Some admire their raw, unadorned look, while others criticize them for being cold and unwelcoming.

Supporters of Brutalism argue for the preservation of these buildings due to their historical and architectural significance. They view them as cornerstones of community identity. Critics, however, focus on aesthetic, functional, and environmental issues, advocating for their demolition.

These debates highlight the complex relationship between urban development, public opinion, and architectural heritage. They show that Brutalism continues to provoke thought and discussion.

Brutalism Today: Revival and Renovation

In recent years, Brutalism has seen a revival. People now recognize its cultural and architectural value. This resurgence often involves adaptive reuse, where old Brutalist buildings get new purposes.

Architects and designers find new uses for these concrete structures while keeping their original look. These projects aim to preserve Brutalism’s legacy and demonstrate its adaptability. They highlight Brutalism’s unique place in architecture and its potential to create livable urban spaces.

Conclusion

Brutalism remains a bold and controversial chapter in the history of architecture. It redefined aesthetics with its raw forms and materials after World War II. Despite criticism and calls for demolition, support for preserving Brutalist structures is growing.

What once seemed like a concrete nightmare is now admired for its historical and architectural significance. As we re-evaluate Brutalism, it continues to show the resilience and flexibility of architecture. This style plays a crucial role in shaping our cities and cultural life.