Project: Mount Desert Island Family Compound

Architects: Baird Architects

Lead Architect: Matthew Baird

Location: Mount Desert Island, Maine, United States

Year: 2021

Photographs: Elizabeth Felicella

Winner of AIA Maine 2022 Merit for Excellence in Architecture Award

Overlooking the ocean on Mount Desert Island, this family compound comprises two houses: A new ground-up structure, House 7, and the preservation of and addition to an existing mid-century modern pavilion, House 9. Commissioned by a family who have visited this coast for many years, the goal of the project was to create a year-round compound for family gatherings and visits by generations to come. The project combines a minimalist vernacular expression with environmentally sensitive systems and construction.

House 9 was originally designed in 1965 by architect Richard Homer, who studied at MIT under Walter Gropius, and who was one of a small group of architects (George Howe, Edward Larrabee Barnes, and George Savage) who brought contemporary architectural thinking to the island in the two decades following World War II.

The project, radical for its time, was conceived as a modern interpretation of the traditional summer cottage, separating sleeping from living and dining pavilions, employing exposed heavy timber frame construction, large expanses of glass, and vertical board and batten siding. We sought to preserve the best aspects of the original house, including retaining the existing unfinished board and batten cladding, which had weathered on the interior. Duratherm was chosen to supply new windows, with naturally weathering teak frames.

The kitchen was relocated from a mezzanine to the lower level and an exterior porch was enclosed to allow more interior space for a single level open-plan kitchen, living, and dining. New sliding glass panels open the living room corner to allow unobstructed views of the ocean.

House 9’s new addition, a three-bedroom, three-bath sleeping pavilion, sits uphill from the 1960’s restored volume, and has a similar palette of Douglas Fir walls, ceilings, and floors, finished in a minimalist expression. The old and new are juxtaposed geometrically and connected by a striking glass bridge.

Next door, House 7 is a new ground up house, overlooking the original structure and the ocean beyond. The layout of the second house relates to the scale of House 9’s interior program, circulation, and formal expression, maximizing natural lighting with expansive floor to ceiling glass. They share a similar material palette and strong geometries – single-pitched volumes sloping up from the landscape and cupped in plan to catch the prevailing sea breezes.

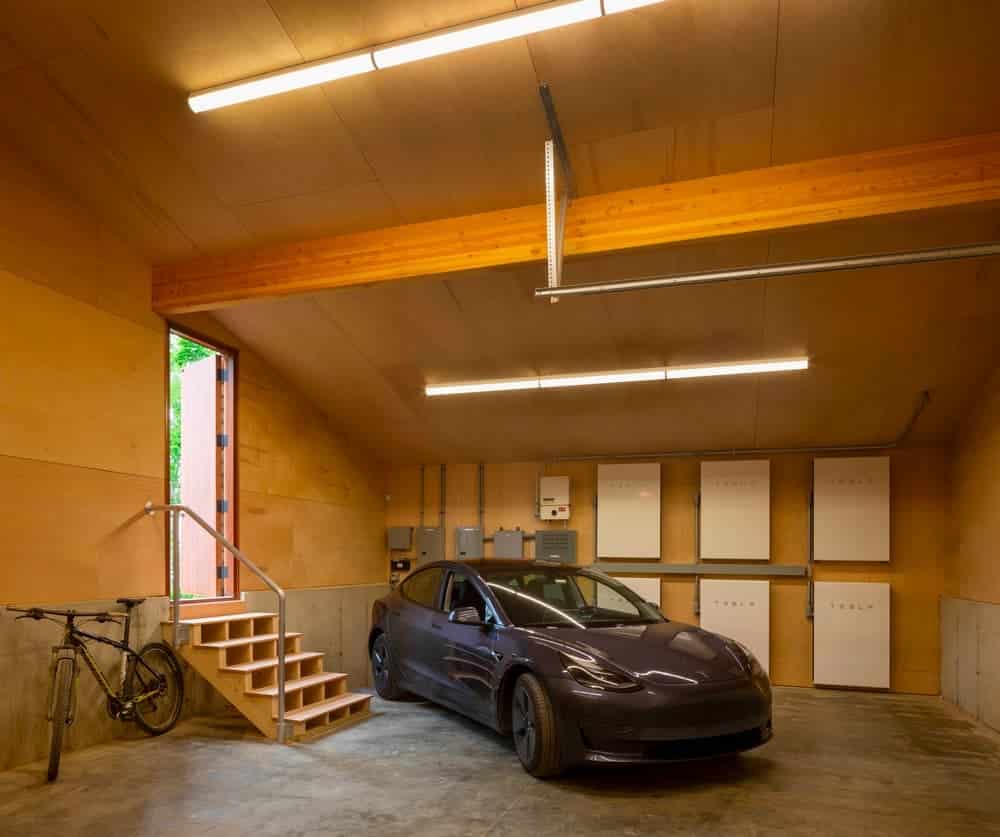

House 7 is equipped with a solar array that feeds both houses: 40 high-efficiency solar panels that charge 6 lithium-ion batteries. Each battery supplies a continuous output rating of 5,000 watts, allowing the complex to operate without grid-tied electricity. It can run all circuits on both houses for five days without sunlight.

The houses have no air conditioning, a mandate of the owner, and instead employ passive cooling strategies. Despite the extensive west-facing glass, both houses can maintain a temperate climate throughout the summer. Whole-house fans amplify the stack-effect cooling, and all bedrooms are equipped with above-door transoms to allow extraction of hot air. Over insulation was achieved using closed-cell soy-based icynene and high efficiency triple glazing.

The geometries of House 7, and House 9 sleeping pavilion, were designed and built with respect for Homer’s original building. The materials used in both houses were inspired by the local vernacular. A stone fireplace was built in each house, constructed of weathered granite salvaged from an abandoned quarry nearby. Landscaping is minimal, employing a thoughtful “return to nature” approach, using indigenous plants.

Deep appreciation for the inherent beauty of Maine’s rocky coastline and a passion for modernism drove the design of these houses. Houses 7 and 9 pose a minimalist vernacular expression that has been well received by the community, asserting contemporary architecture’s ability to transcend rooted traditional aesthetic values.